The major objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of sand mining disturbances on the diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). In addition, the proportional changes in the diversity of AMF to the distances from riverbanks were assessed. For this purpose, the riparian forest of the Maroon River, Iran was divided into three locations with a 200-meter wide zone in between. Thus, the locations studied were named Distance I (riverbank), Distance II (intermediate), and Distance III (farthest from riverbank). In each of these distances, 10 Tamarix arceuthoides and Populus euphratica of each species were randomly selected. At the same time, soil and root samples were collected from the rhizosphere of the tree species studied. Results indicated that totally 13 AMF species were observed in T. arceuthoides and 19 AMF species were recorded in P. euphratica rhizosphere belonging to 6 genera and 6 families. In these AMF species, Glomus segmentatum, G. geosporum, G. rubiforme, G. nanolumen, G. spinuliferum, Claroideoglomus drummondii, Gigaspora gigantea and Acaulospora paulinae appeared only in P. euphratica rhizosphere, while G. multiforum and Claroideoglomus claroideum were observed only in T. arceuthoidesrhizosphere. Moreover, Distance II had the least AMF species both in T. arceuthoides and in P. euphraticarhizospheres, and also the least spore density and root colonization rate. Our results are important in that they provide a list of resistant AMF species that could be used in the conservation of biodiversity.

Riparian forests maintain a chain of important ecological functions, including water purification, flooding control, and natural habitat and biodiversity conservation (Burton, 2006; Harris and Koucher, 2007; Strasser et al., 2014). Nevertheless, they are among the most endangered ecosystems in the world (Tockner and Stanford, 2002). Khuzestan, a southwestern province of Iran, is well known as a home to major rivers and abundant fresh water resources. The littoral lands beside Khuzestan’ s riverbanks are covered by riparian forests, mostly composed of Populus euphratica and Tamarix arceuthoides (Browicz, 1977). These riparian forests, with a high floral diversity (Sakio and Tamura, 2008), are crucial for ecological health in this arid area (Isebrands and Richardson, 2014). In spite of the importance of these riparian forests, little is known regarding the ecological information.

There are several factors causing the degradation of these vulnerable ecosystems, including the invasion of exotic plant species (Naiman et al., 2000), environmental pollution (Tockner and Stanford, 2002) and sand mining (Tockner and Stanford, 2002; Lawal et al., 2011; Sreebha and Padmalal, 2011; Bravard et al., 2013). It is worthy noting that sand mining has been noted to be among the most devastating factors due to the over-exploitation for sand and gravel all over the world. Researchers have found that sand mining may result in the loss of riparian forest (Padmalal et al., 2008), depletion of vegetation, water pollution (Byrnes and Hiland, 1995; Ashraf et al., 2011), landscape disturbance (Lawal et al., 2011) and many other negative effects (Ashraf et al., 2011). However, there is very little available information on the effect of sand disturbances on soil microorganisms, such as the diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in these ecosystems.

AMF are soil-borne microbial communities that form mutualistic symbioses with terrestrial plants (Smith and Read, 2008). They belong to the fungal phylum Glomeromycota (Schü ß ler et al., 2001). These fungi are known to be important for the stability and productivity of ecosystems (van der Heijden et al., 2008). Furthermore, they are crucial for the initiation of vegetation (Caravaca et al., 2003; Quoreshi, 2008). Yet, it should be pointed out that these fungal communities are likely to be affected by vegetation, soil CaCO3, land use, and disturbance (Jha et al., 1992; Lambin et al., 2003; Oehl et al., 2011; Moradi et al., 2015). Therefore, these fungal communities can be used as soil quality indicators (Oehl et al., 2011; Verbruggen et al., 2012).

Recently, researchers have found that AMF can form mutualistic symbioses with some riparian plant species, such as P. euphratica and Tamarix spp. (Yang et al., 2008). The infection rate and status of AMF in riparian forest species were affected by their soil chemical properties (Shi et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008; Moradi et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that AMF spore density, root colonization, and diversity are different in these riparian forests (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010; Lehnhoff et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013). Therefore, we hypothesize that the responses of AMF in different riparian forests to sand mining disturbances are species-dependent. Our aim of the study is to evaluate the effect of sand mining and truck movements on the diversity of AMF in a riparian forest dominated by P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides in Khuzestan, Iran.

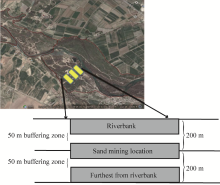

This study was conducted in the riparian forest of Maroon River in Behbahan within Iran’ s southern Khuzestan Province. The study site was located at 32° 38'53"-30° 39'30"N and 50° 09'30"-50° 10'25"E with an average elevation of 250-300 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1). The average annual precipitation and annual mean temperature of the site were 350 mm and 24° , respectively. This site was typically dominated by P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides with a floral coverage by other species like Lyciumsp. and Vitex pseudonegundo to a lesser degree.

The riparian forest along the width direction was divided into three zones with a 200-meter wide zone in between. The locations studied were named Distance I (riverbank), Distance II (intermediate), and Distance III (furthest from riverbank). The reason behind this division was that sand mining and truck movements took place within Distance II. To differentiate the distance effect from the disturbance effect, we have left 50 meters as a buffering zone between each of the distances studied. On the other hand, we have left 50 meters before and after sand mining locations as a buffering zone (Fig. 1). Since the dominant species in this riparian forest were P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides, we randomly selected 10 trees from each species per studied distance (in total 60 samples, 30 samples for each species). Rhizosphere samples were taken from a depth of 15 cm after litter removal in spring (Moradi et al., 2015). These soil samples were used for spore extraction and the determination of soil physical-chemical properties.

Spores were extracted from the soil by wet sieving and decanting (Gerdemann and Nicolson, 1963), followed by centrifugation in water. Sieve sizes ranged from 38 to 500 µ m. Five grams of the rhizosphere soil of the plant species studied were used in extracting spores. All extracted spores were mounted on slides stained with PVLG (polyvinyl alcohol lactic acid glycerol), as well as PVLG with Melzer reagent. The identification procedure was based on the observation of morphological features like spore walls, colors and sizes using a stereomicroscope (Olympus CH-2) and in accordance with Schenck and Perez (1988).

All soil samples were air-dried and passed through a 2-mm sieve. Soil phosphorus (P) (Olsen et al., 1954), exchangeable potassium (K) (Morwin and Peach, 1951), nitrogen (N) (Bremner and Mulvaney, 1982), organic carbon (OC) (Walkley and Black, 1934), pH (deionized water suspension of 1:2.5) and textures (hydrometric) were determined. Soil moisture content was determined using oven drying at 105° C for 24 h.

AMF diversities were evaluated using the Shannon-Weiner indices of diversity (H’ ), evenness, Simpson’ s index of dominance, and Margalef’ s richness index (Eqs. 1-4).

$H'=-\sum{{{P}_{i}}}\ln {{P}_{i}}$, (1)

where Pi is the relative abundance of each identified species per sampling site.

Evenness (E) was calculated by Equation 2:

$E=\frac{H'}{{{H}_{\max }}}$, (2)

where Hmax=log2(S), and S is the total number of species.

Simpson’ s index of dominance (D) was calculated by Equation 3:

$D=\sum{\left[ {{n}_{i}}\left( {{n}_{i}}-1 \right)/N\left( N-1 \right) \right]}$, (3)

where ni is the number of spores of a species and N is the total number of identified spore samples.

Margalef’ s richness index (Dm) was calculated by Equation 4:

${{D}_{m}}=\frac{S-1}{\ln (N)}, $ (4)

where S is the number of species.

All data were subjected to normality tests and analyzed using one-way ANOVA to determine any differences between diversity indices and physical-chemical soil properties within the denoted distances. If data were significantly different, a pairwise comparison was conducted using the Duncan’ s post hoc analysis. Moreover, the Pearson’ s correlation coefficient was used to determine any significant correlation between the soil parameters and AMF diversity indices. All the analyses mentioned were performed by SPSS 16.0 software. Furthermore, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to obtain the most important factors on AMF diversity. To evaluate the effects of soil physical-chemical properties, we applied redundancy analysis (RDA) with Monte Carlo (unrestricted 999 permutations) to verify the relationship between AMF diversity indices and soil physical-chemical properties. This analysis was performed using the CANOCO for Windows version 4.5. Also, PC-ORD for Windows (V.5) (McCune and Mefford, 1999) was used to determine the keystone species in the study field.

The results indicate that there were 21 AMF species belonging to 6 genera and 6 families in the riparian forest (Table 1). Thirteen species were observed in the T. arceuthoides rhizosphere and 19 in the P. euphratica rhizosphere. As shown in Table 1, Glomus segmentatum, G. geosporum, G. rubiforme, G. nanolumen, G. spinuliferum, Claroideoglomus drummondii, Gigaspora giganteaandAcaulospora paulinae appeared only in the P. euphratica rhizosphere. Meanwhile, G. multiforumandC. claroideum occurred in Tamarixsp. rhizosphere (Table 1). Glomus was the most frequent genus observed in stands of T. arceuthoides and P. euphratica, being consistent with the finding of Bö rstler et al. (2008). It should be noted that some AMF species are plant species-specific for T. arceuthoides and P. euphratica. The reason for this may be related to health of host plants and/or soil conditions that may affect AMF diversity (Chaudhary et al., 2008). Another reason for this may be due to genetic differences among different AMF species, since such a difference could affect the survivals or functionalities of AMF and their host plants (Colard et al., 2011).

The T. arceuthoides rhizosphere had 9, 6, and 11 AMF species detected in Distances I, II, and III, respectively, while they were respectively 11, 9, and 13 AMF species in the P. euphratica rhizosphere, indicating that Distance III (i.e., the farthest research zone from the riverside) had the highest AMF, while Distance II or the zone severely disturbed by sand mining had the least AMF. Moreover, G. geosporumandG. rubiformewere AMF species that were only detected in the P. euphratica rhizosphere within the boundaries of Distance II. It means that the tolerance of these AMF to disturbance may be useful for later restoration activities (Lara-Pé rez et al., 2014). We also found that F. badium, F. constrictum, and C. etunicatum were among AMF whose frequency remained unaffected by the distance from the riverside and the location of sand mining. This result may indicate that these fungi have adapted well to these anthropogenic disturbances. In contrast, the distance from both the riverside and the sand mining had negative effects on the frequencies of F. mossea, G. gibbosum, G. nanolumen, G. spinuliferum, C. drummondii, A. trappei, and P. fransiscana (Table 1). These AMF may well be the indicators of land degradation (Kennedy and Papendick, 1995). Based on this study, a list of AMF species can be proposed both for disturbed and for non-disturbed distances. This kind of list can be important because it may be helpful for site restoration (Symanczik et al., 2014).

| Table 1 AMF and their frequencies (%) within the designated distances |

F. badium and G. gibbosum were identified as the keystone indicator species at Distance III, while no keystone species were found at the other two distances in the P. euphraticastand (Table 2). It is well documented that AMF are keystone soil micro-organisms for the conservation of biodiversity (O’ Neill et al., 1991; Power and Mills, 1995; Piraino et al., 2002). The lowest frequency of G. gibbosum at Distance II (i.e., the severely disturbed distance) indicated that the negative effects of sand mining on keystone species are rather pronounced. Our results are important in that they provide a list of resistant AMF species that could be used in the conservation of biodiversity.

In the T. arceuthoides stand, G. gibbosum and C. etunicatumwere considered as keystone species in Distance I and Distance II, respectively (Table 3). This finding is consistent with the findings of Piraino et al. (2002), who provided evidence that C. etunicatum occurred in a highly disturbed environment. Different AMF keystone species found in P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides stands reflect not only the differences in responses to plant species but also the AMF symbiosis to anthropogenic activity.

The changes of AMF species by anthropogenic regimes suggest that AMF is a good indicator of soil quality changes, being consistent with the findings of Verbruggen et al. (2012).

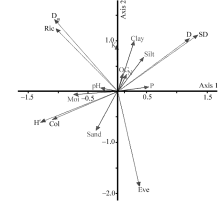

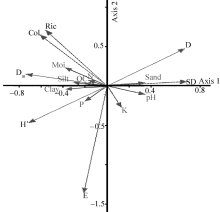

The PCA results for T. arceuthoides indicated that the first and second axes explained 48.80% and 23.46% of total variance, respectively (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the results of Monte Carlo permutation tests on redundancy analysis (RDA) showed that soil sand, silt, moisture, clay, and phosphorus (P) are the most important factors affecting AMF diversity inT. arceuthoides(Table 4). The PCA result for P. euphratica revealed that the first and second axes explained 69.27% and 19.71% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 3). The Monte Carlo permutation tests on RDA indicated that the most significant affecting factors in the physical-chemical properties of soil on AMF diversity in P. euphratica stands are soil moisture, clay, and pH (Table 5). Our results are consistent with Deepika and Kothamasi (2015). These results imply that soil-property changes caused by anthropogenic activity can result in significant AMF changes. Furthermore, it implies that sand mining disturbance affects AMF directly and indirectly by changing either soil conditions or the status of host plant roots.

| Table 2 Keystone indicator species for P. euphratica stand |

| Table 3 Keystone indicator species for T. arceuthoides stand |

| Table 4 Monte Carlo permutation test on redundancy analysis for soil physical-chemical properties of T. arceuthoides |

The SD associated with the T. arceuthoidesrhizosphere in Distance II, where sand mining and truck movements occurred, had the highest significant value (Table 6). Nevertheless, no significant difference was observed in SD values with regard to P. euphratica (Table 7). The higher SD in Distance II may be explained by soil compaction that reduced root growth (Wallace, 1987; Trejo et al., 2016). In the present study, P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides showed different SD and root colonization rates, reflecting the fact that different plant species respond differently to these two factors (Li et al., 2007).

Furthermore, a high level of symbioses was observed between AMF and P. euphratica, being in accordance with the findings of Wang et al. (2010). Yet, our results are not in accordance with those of Yang et al. (2013) who reported a significantly lower SD in P. euphratica rhizospheres. The reason for a significantly higher level of SD in the current study may be attributable to a higher AMF diversity compared to Yang et al. (2013). The minimum and maximum colonization rates for T. arceuthoides and P. euphratica were observed at Distances II and III, respectively (Table 6). A clear indication of the negative effect of sand mining and truck movement was found on root colonization rates at Distance II. Changes in SD and root colonization may be induced by soil physical-chemical changes caused by sand mining activity. This study provides a much improved understanding of the impact of sand mining on AMF diversity, colonization, and SD.

An increasing trend in the root colonization rate with increasing distance from the river was observed in the present study, which probably indicates that soil conditions were improved for AMF symbiosis farther from the river. High level of root colonization in this study is in agreement with the findings of Wang et al. (2010).

| Table 5 Monte Carlo permutation test on redundancy analysis for soil physical-chemical properties of P. euphratica |

T. arceuthoides stand had the least AMF diversity at Distance II (Table 6) and P. euphratica stand had the highest AMF diversity at Distanced III (Table 7). Although, Shannon-Weiner indices of diversity (Hʹ ) and Simpson’ s index of dominance (D) displayed no significant differences between the triple designated Distances, the least significant D was observed in Distance II (Tables 6 and 7). The reason for this is that D is affected by species richness (Magurran, 2004) and higher species richness results in a higher D value (Mahecha-Vá squez et al., 2017). As the least species richness was observed in Distance II and then the least D was also observed in this zone (Stü rmer and Siqueira, 2011). These results suggest that the impact of sand mining was severe enough to have negatively affected AMF diversity in riparian forest. Sand mining resulted in changes in AMF diversity and composition, and this knowledge is crucial to the understanding of mycorrhizal function in these ecosystems (Soka and Ritchie, 2014a, b).

In addition, distance from the local river also affected AMF diversity, while Distance III (the farthest distance from the river) hosted the highest AMF diversity. This may be due to the least negative effects of natural phenomena among the three distances.

| Table 6 AMF diversity for T. arceuthoides stand |

| Table 7 AMF diversity for P. euphratica stand |

Pearson’ s correlation between soil factors and AMF diversity indices at the P. euphraticastand revealed that AMF richness had a positive correlation with soil P and a negative correlation with pH. However, evenness had a significant negative correlation with richness, Simpson’ s index of dominance (D) and Margalef’ s richness index (Dm). Furthermore, soil moisture had significant negative correlations with root colonization and AMF richness, while, had a negative significant correlation with spore density (SD) (Table 8). However, for the T. arceuthoides stand, AMF richness had a significantly positive correlation with root colonization (RC). Soil phosphorus (P) had a significantly positive correlation with D and a significantly negative correlation with Shannon-Weiner indices of diversity (H’ ). Yet, Margalef’ s richness index (Dm) was significantly correlated with root colonization. Also, soil moisture had a significantly positive correlation with root colonization (RC) and a significantly negative correlation with SD (Table 9). These results indicate the importance of better soil conditions for higher AMF diversity (Mirzaei and Moradi, 2017). Also, in this study, Distance III with better soil conditions and less anthropogenic activities had higher AMF diversity.

| Table 8 Pearson’ s correlation between soil parameters and AMF diversity indices at P. euphratica stand |

| Table 9 Pearson’ s correlation between soil parameters and AMF diversity indices at T. arceuthoides stand |

Several factors were reported to have affected AMF diversity, such as environmental (Moradi et al., 2015) and soil conditions (Yang et al., 2011). But in the present study, sand mining and truck movement were documented to have resulted in AMF variations. Also, soil P and pH affect AMF diversity, being in line with the findings of other studies (Treseder, 2004; Yoshimura et al., 2013). Being similar to previous studies highlighting the use of AMF species as soil bio-indicators (Fokom et al., 2012; Vasconcellos et al., 2016), the present study has also demonstrated that AMF diversity could be a key factor for understanding soil quality. Furthermore, it should be reiterated that because fungi are able to adapt to local habitats and also because they are important for biodiversity conservation, AMF species should be carefully identified for each specific region (Symanczik et al., 2014).

Unlike other studies reporting that soil compaction did not affect AMF (Miransari, 2013; Thorne et al., 2013), the present study demonstrated that sand mining and truck movement did negatively affect AMF diversity and SD through reducing fine roots (Waltert et al., 2002). As shown earlier, sand mining caused approximately 24.4% and 10.8% reductions in SD in P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides, respectively. These results are in accordance with Jasper et al. (1991).

The present study found that disturbances by sand mining and truck movements in riparian forests negatively affected AMF diversity and root colonization rates. Although the study site was only 400 meters long, the results displayed a high spatial variation in AMF diversity, suggesting that the riparian forests are rather sensitive to anthropogenic activities. Furthermore, this present study show that soil moisture, clay, silt, sand, and P are among soil factors that can significantly change AMF communities both in the rhizospheres of P. euphratica and T. arceuthoides. In addition, the distances from the local riverbank also played a part in the variation of AMF diversity.

We thank Behbahan Khatam Al-Anbia University of Technology for its support during this study.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

|

| [45] |

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| [48] |

|

| [49] |

|

| [50] |

|

| [51] |

|

| [52] |

|

| [53] |

|

| [54] |

|

| [55] |

|

| [56] |

|

| [57] |

|

| [58] |

|

| [59] |

|

| [60] |

|

| [61] |

|

| [62] |

|

| [63] |

|

| [64] |

|

| [65] |

|

| [66] |

|